In a recent interview with The Times, acclaimed theatre director Robin Icke said that he walks out of shows at the interval ‘all the time.’ For the audience viewing his startling new play The Red Barn, he makes this choice rather more difficult, if not impossible – the two-hour long production, currently being staged in the National Theatre, has no interval and a no re-admission policy. An appropriate choice seeing as freedom, or the lack of it, is subtly and ambivalently explored in this unsettling psychological thriller.

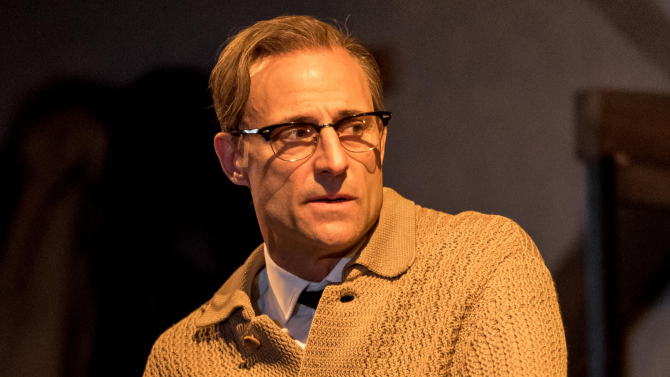

This delicate retelling by David Hare of Belgian thriller writer Georges Simenon’s La Main is not so much a classic-whodunnit but a keyhole-look into the devastations of male inadequacy, sexual jealousy and existential freedoms. It begins in a snowstorm in Connecticut, with two couples fighting their way home after a cocktail party. One of the men does not make it back and it falls on the remaining man to find him. Instead he whiles away the time sat smoking in the red barn before returning alone. It is the consequence of this that causes his life as he knows it to unravel. Mark Strong is chillingly brilliant as the disappointed, crippling inadequate, middle-aged Donald Dodd. Raised in a provincial village he was never able escape and trapped by his own normalcy and convention, he is a man who has ‘lived my whole life with the handbrake on’. Always overshadowed by his effortlessly successful friend Ray (Nigel Whitney), he now finds himself falling in love (or fascination) with Ray’s elegant and lifeless wife Mona (Elizabeth Debicki).

The production is a glamorous, icy affair. However, Mona’s glacial Manhattan apartment and the cold-hearted Connecticut cocktail party, the smoke and mirrors, are not able to hide the cracks for long. David Hare has been a long-time fan of Simenon’s work and has embraced all of his deadpan flatness. Simenon took the advice of his mentor, Colette — ‘Get rid of all the literature, and you’ve got it’ — his work is the bare bones and inaction is the tool with which he explores psychological discomfort. To dramatise a work so bare on action and vocabulary and to spread it over two hours has been cleverly tackled by the team behind this production. The clinically artistic design by Bunny Christie indulges our voyeuristic tendencies as we uncomfortably peer into the cracks of the characters’ private lives. With the use of black panels skilfully contracting and expanding into different sizes, sometimes closing in from the ceiling and other times from the side of the stage; the suffocating effect of framing of the characters induces a sense of dread. It is aesthetically thrilling and cinematic; think peeping-Tom James Stewart in Hitchcock’s Rear Window. Not only does it force the gaze by limiting the sense of perspective and point of view of the audience, but it physically traps the characters. Once again the theme of freedom, or lack of it comes to the fore. Known to be a film-buff, it is hardly surprising that Icke has painted this production in shades of film noir. Tom Gibbons’ sound design also quickens the pace with a ticking clock and radiator hums in the background, heightening the frustration of the characters who have no escape; from time or from the audience.

This is America in the 1960s – a decade where hopes of a Golden Age came crashing down. Political turmoil, the Vietnam War, the hope of sexual liberation and the civil rights movement promised freedoms that were empty; for the problem with freedom is learning to distinguish just enough from too much, beware the catch, as often it is a dangerous one. This is where Simenon’s European sensibility met the “American dream”. Simenon spent some time living in Connecticut in the 1940s and was stimulated by the dramatic changes in American society. This experience was to live on in his imagination and feature in his work throughout his life. For Simenon, sexual politics was just as murky as politics. Time and time again he presented the quintessential central male character being lured from the stultifying cocoon of himself — and his suburban, oppressively domesticated life — into a wider, world of sexual peril, where his newfound freedom is more than he can handle. Simenon kills both his victims and culprits slowly.

Icke has shown his nerve and once again has done theatre in his own way: his focus lens zooming in, highlighting the bits he wants us to see has a flair of genius, but at times does seem like overkill. The joyful thrill of Simenon’s book was that it was written in first person; Icke, Hare and Christie have ingeniously tackled this, but still the production feels restrained. Like Donald’s life the action moves at a painfully unhurried pace. Mark Strong exudes the hidden, if not understated explosiveness of Donald and Hope Davis lightens the part of cheated wife with the injection of muted humour. It’s all very well crafted and beautifully styled but it will leave you feeling cold.

By Lucy Binnersley

The Red Barn by David Hare

The National Theatre

Until mid-January

You must be logged in to post a comment.