Jamie Cameron

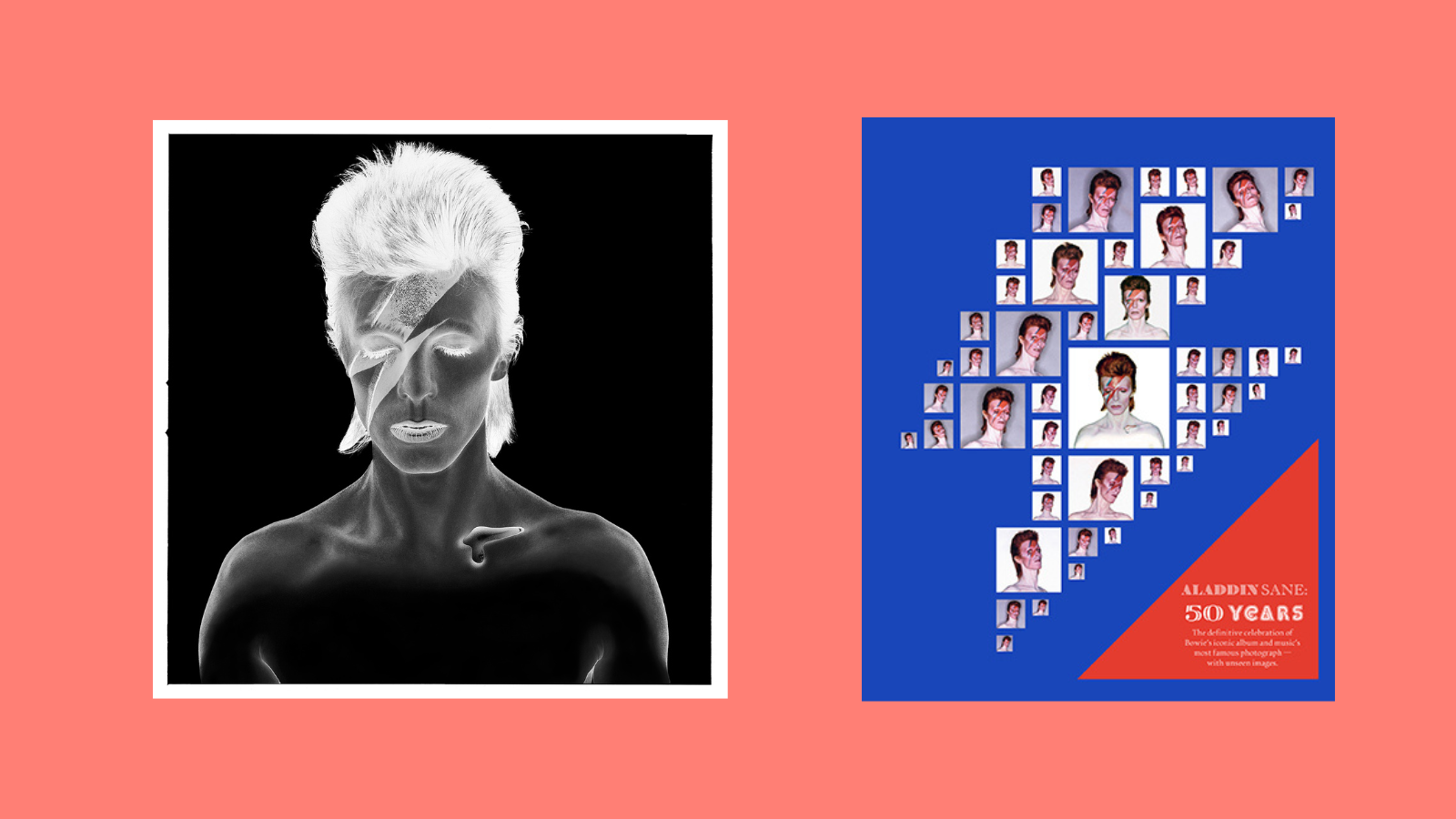

The London Magazine speaks to Geoffrey Marsh, curator of a new exhibition at the Southbank delving into the creation of Aladdin Sane’s iconic ‘lightning bolt’ cover portrait by Brian Duffy, fifty years on from the release of the album.

Q. I wanted to start off with talking a bit about how this exhibition came to be, obviously it coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Aladdin Sane, but how did you approach trying to capture the totality of what Bowie was as an artist, which is, of course, vast in its scope?

A. Well, I did the ‘David Bowie Is’ exhibition 10 years ago at the V&A and that rather took over one’s life for a couple of years, so I had a long break from it. But I was talking to Chris Duffy who owns his father’s photo archive and manages it. We were talking about the various photo sessions that Bowie did with Duffy. And the idea sort of came up of doing something for the 50th anniversary of Aladdin Sane because it’s such an extraordinary image.

But obviously, the exhibition, which is in the basement of the Royal Festival Hall, isn’t a museum, it’s an art centre. When we started talking to them it became clear that they wanted something which was about the art on the cover, not just about the history. I think that’s what’s so interesting, to look at how this image emerged as a single photograph from a series of almost accidents. You have David, who was very, very ambitious – this was his first album after Ziggy Stardust – and he was really, for the first time, a star. So he was obviously trying to think about what his image should be with that. And in Duffy, he had a photographer who was very experienced in photographing for fashion and portraiture. Out of that combination came this extraordinary image. I think it’s something you can see right through David’s career: his ability to find people to work with, and once he’s happy with them, trusting them totally.

When this photograph was taken, David had just come back from America. He was finishing off a UK tour, finishing off the album itself and then rushing back to America and then onto Japan. So, this photo shoot was taken when he was fantastically busy. Once he did the photograph, he very much left it to Duffy to finish it off.

You mentioned that you were working alongside Chris, Brian Duffy’s son, on the exhibition. What was that like? Did it offer a more immediate connection to the work itself?

I think so, because obviously, Duffy was quite a character <laugh>. David famously said of him that aggravation and Duffy go together like Gin and Tonic. He was one of that group of essentially working class photographers who came from quite ordinary backgrounds, but who just took over the photographic scene in London in the sixties: Terrence Donovan, David Bailey, Duffy, and others. So it was very much a meeting of equals. Duffy photographed David in his Ziggy Stardust outfit the previous year, so it wasn’t that they hadn’t met or anything. In fact, it was clear that David very much trusted Duffy because obviously for fashion shoots and things you would’ve brought in props and all the other things that they might need in the studio. But there weren’t props for this photo shoot, he decided just to use his body, and that’s what came out as a result.

There are some amazing stories about Bowie’s production team splurging as much money and effort on this album cover as possible to ensure that RCA would promote it widely. You mentioned how this exhibition is very much focused on the image. Did you want to weave these types of stories in as well? Or was it always about centring the image?

Well, I think it’s really all about the image because it is such an extraordinary, almost, icon nowadays. It’s sort of moved out of just Bowie’s world. It’s appeared with Kate Moss and even the Queen has appeared with the zigzag on her face, so it has sort of moved into a different realm. And I think that was what we were interested in trying to question, why that had happened? And, secondly, what is its significance today? Because we’re at a period when ideas about gender and identity and how you present yourself are absolutely crucial. But back in 1973, when the photo was taken there’s no internet, there’s no social media, to most of us photography was something that was done by other people, to other people.

Now we live in a kind of image saturated world. And in fact in 1973, only 45% of houses in Britain had a telephone even. So, for other people it was go to your neighbor or go down the call box. So part of it was showing how this image has tracked over this extraordinary period when the internet and social media has made us all sort of performers in our own right.

I think what’s really crucial is David created this very enigmatic look which Duffy then finished off with the airbrushing and everything else. But it’s the image, really, I think, that’s stuck. And clearly the fact that David’s got his eyes closed is quite extraordinary. It’s against the whole tradition of Western portraiture because of the idea that you, your eyes, are the way to look into your soul. Famously Chris Levine took a photograph of the Queen in 2007, ‘Lightness of Being’, with her eyes closed, which was also quite extraordinary.

But none of that I think was probably planned. At the time, and in the images shown in the exhibition, most of the shots were turned to the left, turned to the right, profile shots. There were only a couple actually with the eyes closed image. And of course, at the time, there was no digital photography, so the film had to be sent out for processing. So although they probably took Polaroids at the time, which have not survived, there was no certainty about what sort of image was going to come out of this. But it’s quite clear as soon as the contacts came back that Duffy recognised that the eyes shut image was one to use, and that’s the one he worked with.

That’s amazing, and really the magic of film photography I suppose. My final question, and this one is slightly indulgent, but I thought with this exhibition, and obviously ‘David Bowie Is’, and the other things you’ve done, you are probably one of the best people to ask this question to… so can I ask, what is your favourite Bowie album? Do you have a favourite? Is it Aladdin Sane?

Oh gosh, that’s so hard. Um, I have a favourite Bowie song? Can I answer that? It’s a song which actually a lot of people don’t know, which is ‘Memory of the Free Festival’, recorded in 1969 about the free festival he put on at Beckenham, which he put on at the same time as Woodstock was happening in America. Obviously it was a much smaller event, but I love that song because in it he’s lying on the ground, looking up at the sky in London. My son was running in the marathon this weekend and I was up at Greenwich Park sitting there rather imagining a similar sort of situation. And I think it captures that extraordinary feeling when you are in your late teens or twenties about the absolute potential of life – you can do anything. Bowie wasn’t fazed by the fact that Woodstock was gonna be the largest gathering of people for a peaceful purpose at the time. He was doing his own thing. He was quite content just pushing what he was doing and letting other people get on. And I think that’s the key thing about Bowie, he always said, don’t copy me. Look at what you want to do yourself and just get on and do it. And I think that applies to how people look nowadays. One of the interesting things in the exhibition is the comments book at the end where so many people have said that it was Bowie who sort of liberated them, to be what they wanted to be, but also, to look like they wanted to look.

Thank you for speaking to us Geoff.

Thank you.

To discover more content exclusive to our print and digital editions, subscribe here to receive a copy of The London Magazine to your door every two months, while also enjoying full access to our extensive digital archive of essays, literary journalism, fiction and poetry.