Angela Carter

The Who

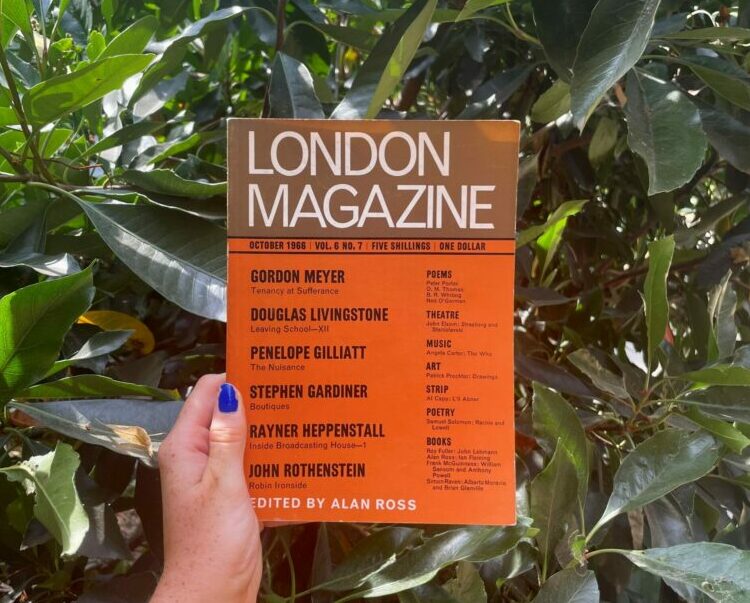

From the archive, the following review of rock band The Who by Angela Carter was printed in the October 1966 issue of The London Magazine edited by Alan Ross. Angela Carter was an English novelist, short story writer, poet and journalist, perhaps best known for her collection of short stories, The Bloody Chamber (1979).

When they turn on the crimson lights, it is like being in the heart of a rose. It is very warm and very dark and very velvet underfoot. Velvet, that is, except where it has been made nicely slippery for the dancers. It is so hot that a balloon pops dead in the net of ballons on the ceiling and the exhausted shred of rubber floats softly past the laden balcony onto the packed heads below, as if all those waiting down there were so many babes in he wood and ths a leaf dropped by a friendly robin. Tonight, there are a lot of people in the ballroom, in fact, it is a full house; and there is hardly any dancing, now, only a few dizzy birds shaking at one another on the fringes of the crowd, and everyone is still and waiting because it is time for our fabulous guests, give them an I-love-you-welcome ‘The Fabulous Who.’

The revolving stage revolves, bearing away, like the wrath of God, the announcer in his rumpled white suit just as he extends his welcoming arms. The screaming starts, and here! are The Who, arriving in a shock of noise. The Who blast the screaming into inaudibility. Who would ever think that two guitars, only, and a set of drums could make such a lot of noise. It is because of electronics, of course. Look at all the amplifiers, all the banked equipment around them. They can make their noises louder and make different noises louder by adjusting switches.

(Peter Townshend said: “The discords aren’t really intentional. I’d rather have a pure sound.’ Off-stage, he seems younger than in performance, early twenties rather than mid-twenties, friendly but wary. He will not be patronized. He drinks coca-cola from the bottle, after the show. His feet are strikingly slender, elegant and nicely shod. He is the very big lead guitarist and writes a great many songs and is the leader of the group.)

Townshend wears a red shirt on the stand. So does the bass guitarist. They are both quite simply dressed. The drummer has a black pudding basin fringe and, offensive/defensive, he crouches over the drums which form the apex of the group and he wears white trousers and a tee shirt. Something is written on the tee shirt but I can’t see what it is. The drummer’s name is Keith Moon. The vocalist is the most flamboyantly dressed and is the centrepiece. His name is Roger Daltrey and he is yellow-headed. He wears crisp white it bellbottoms and a white shirt and he shines like a star.

None of them smile. They never smile in public. They never smile in photographs. They have a non-smiling image, in fact, an impassive, even an inscrutable, image. First of all, they were mods. Then there of weren’t any more mods, suddenly. After a time, they began to wear pop-art sweat shirts with targets on them and jackets made out of Union Jacks, but they dropped them like hot bricks when pop-art clothes caught on.

It was cheap, overnight. Now every Tom, Dick and Harry, practically has a Union Tack jacket. However, The Who gained some notoriety for putting pop-art into pop.

The stage of the ballroom is all over gilding, fairy lights and mini-turrets, a plastic bower for Walt Disney’s version of Guinevere. Two very big men sit on the edge of the stage and glower at the throng of fans. There is a hefty barrier between the stage and the audience and the screamers thrust against this, urgently, waving their hands, for there is no room to do more. It is a rare group that gets screams in ballrooms, these days. Townshend wrote ‘My Generation’ which had this stuttering bit, ‘Why don’t you f-f-f-f-fade away…’ and the punch line was ‘Hope I die before I grow old’. This was a hit towards the end of last year. Then they went to Chartsville again, earlier this year, with “Substitute’, which begins:

You think we look pretty good together,

You think my shoes are made of leather,

But I’m a substitute for another guy,

I look pretty tall but my heels are high,

The simple things I say are all complicated,

I look pretty young but I’m just

back-dated.

(“The hit parade is important, you see, because we work better when we’ve got a record selling well and there’s the impetus to rehearse more and we get bigger crowds and more interesting work and it’s not just ballrooms, ballrooms, ballrooms. Ballrooms are hell.’ Townshend wrote “Substitute’.)

There is so much screaming during numbers that the audience does not bother to applaud between each one of these immense shifting blocks of sound. Each number is aural crazy paving being bulldozed away. Dancing ceases. In the musky dimness, the square window, where the cloak-room girls sit, looks like a projection from a colour film; the plain light seems too bright and soft, the colours too fresh, to be truly real.

Townsend makes patterns with his free arm, the one that is not holding the guitar. He makes interesting circles and squares and angular shapes with his arm windmilling or pointing. Then he turns to adjust, with a flourish, the amplifiers. The level of sound screeches past the pain threshold. It is excruciating. He holds it and holds it and holds the sound on the exposed nerve for an endless moment and then at last lets it settle to normal. Which is simply loud.

(Townshend says he listens to everything, all kinds of music. He likes Shostakovich and Stockhausen. He’s heard Schoenberg and the twelve tone composers but he doesn’t like them very much. He has grey eyes and is pale, his nose is beaky, it is a London face. They all come from Shepherd’s Bush. He is very thin and his movements are nervy when he talks, which he does swiftly and intelligently. He makes a lot of these Holden Caulfield gestures indicating an awareness of frustrated communication. After the show, behind the stage, the bass guitarist, John Entwistle, who used to play french horn in the Middlesex

Youth Orchestra, is flaked out on a chair, eyes closed. It is exhausting work. The drummer rubs his sweated back dry on a towel. A couple of blonde birds are just sitting around.)

They tend not to give introductions to their songs or to say “Thank-you’ to the audience. They do a Beach Boys’ number, Ba-Ba-Ba-Ba-Bar-bara Anne’. It must appeal to them because of the stutter. The Beach Boys are not like The Who. The Beach Boys are a brash and clean-limbed All American group whose image is one particular American dream, surfin’; lazin’; neckin’, golden sands, golden bodies, beach love, I hate my dad cos he broke up my surf board. Kind of noble savagery ‘Rockin’ an’ a-rollin’, rockin’ an’ a-reelin’, Bar’bra Anne. Ba-Ba-Ba- Ra-Bar’bra Anne.’ Not a bleat, but staccato, possibly a round of machine gun fire or a motor-cycle revving up of a motor boat engine turning over. ‘Ba-Ba-Ba-Ba’.

The Who expel the four syllables cleanly as sucked cherry pips, round, hard and entirely polished of meaning. The words are shapes, merely, no longer symbols. It is a process of abstraction. Word is sound. Pierre Albert Birot once composed a poem to be howled and danced. Roger Daltrey, stiff as a rotating totem pole, dances. His white back squarely to the audience, he stiffly genuflects to the drums and thwacks the cymbal with preposterous vigour. It is preposterous because it is a gesture in a silent movie, who could hear a little cymbal, now, however hard you hit it? The hems of his wide bellbottoms swish and quiver.

(‘Will you just sign these for the kids?’ Townshend accepts a pile of autograph books and slips of paper. His signature is stylized, swift and automatic. The kids are waiting outside at the door like wolves, a gaggle of them, all hungry. It is as if The Who, who have made it so young, have a magic about them which will rub off onto you if you touch them. Not that any will get to touch them, but they will get these autographs, which are relics. “It seems a kind of honour to me, to perform. And it is a direct confrontation with the audience. You are out there in front of them, there aren’t any barriers, nothing between you and them and you’ve just got to work, haven’t you, to work as hard as you can.”)

One person in the crowd-I can’t tell whether it is a boy or a girl-has gone wild and mad and throws white, round arms, high, high till the fluttering convulsive hands on the ends of the arms are nothing but pigeons flying around in the powdery white spotlight and the long hair shakes in regular spasms. Like wooden men or like robots, The Who make sci-fi sound, sounds which clash like colours, orange on mustard on violet on the sharpest that used to be a blues. It must be left over from when they did what was billed as ‘maximum r & b’ (or rhythm and blues to you.) John Cage, the composer, wrote that the composer must ‘set about discovering a means to let sounds be themselves rather than vehicles for manmade theories or expressions of human sentiment’. A fainted girl is carried away over the heads but I think she fainted from heat rather than emotion.

(What we do isn’t even anti-art. It’s got nothing to do with art. I mean, you can say a baby can paint with its fingers or even–you could. say what great patterns it makes when it shits on the floor, and, yes, it’s great but it isn’t art. You can say it is but it isn’t. What we do, what we are trying to do with the music, is changing all the time. Every day. It is part of this fantastic world of pop, which is so new. I was at art school for four years and all I got out of it was learning about auto-destructive art. Art school was a punch in the guts. You started with drawing a straight line and ended up with cybernetics. But at least I learned about auto-destructive art.’)

At the close or climax of the act, they break up their equipment. With manic deliberation, Townshend puts his guitar through an amplifier. The amplifier groans and gapes. Then the microphone the singer is using comes apart and I am not quite sure if this is part of the act or not. Daltrey continues to dance on the spot, unmoved, holding a piece of the microphone.

The revolving stage revolves once again and they spin like the world, smashing up their gear in a final paroxysm of noise until they are out of sight. ‘Exuberance is beauty”, Nonesuch edition of Wm. Blake’s complete poetry and prose, p. 185. This orgy of destruction should come as catharsis, a tremendous release of wound-up tension. Tonight, this time, it doesn’t come off. They seem peeved rather than impassioned, in the grip of a petty irritation rather than an overwhelming frenzy. No exuberance. Sorry, no beauty. Not today. Try again tomorrow.

(“The smashing-up didn’t come off tonight. That was because we had a lousy evening. We couldn’t get tuned up properly, for one thing, and had to keep farting around during numbers, trying to get in tune.’)

Morecambe tomorrow. Ballrooms, ballrooms, ballrooms. Townshend, his coca-cola finished, falls silent and inspects his suave feet which are wearing such shiny brown shoes.

To discover more content exclusive to our print and digital editions, subscribe here to receive a copy of The London Magazine to your door every two months, while also enjoying full access to our extensive digital archive of essays, literary journalism, fiction and poetry.