The following essay was first published in The London Magazine, November 1968, Volume 8, No. 8, with accompanying illustrations, and edited by Alan Ross and assistant editor Hugo Williams.

Simon Watson Taylor

Apollinaire

1880-1918

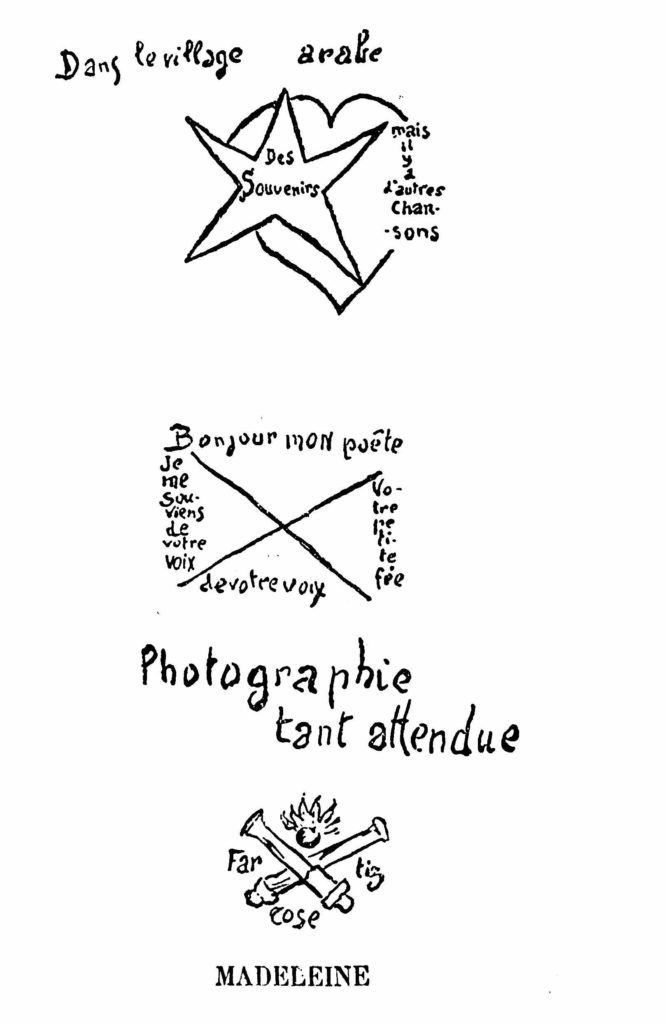

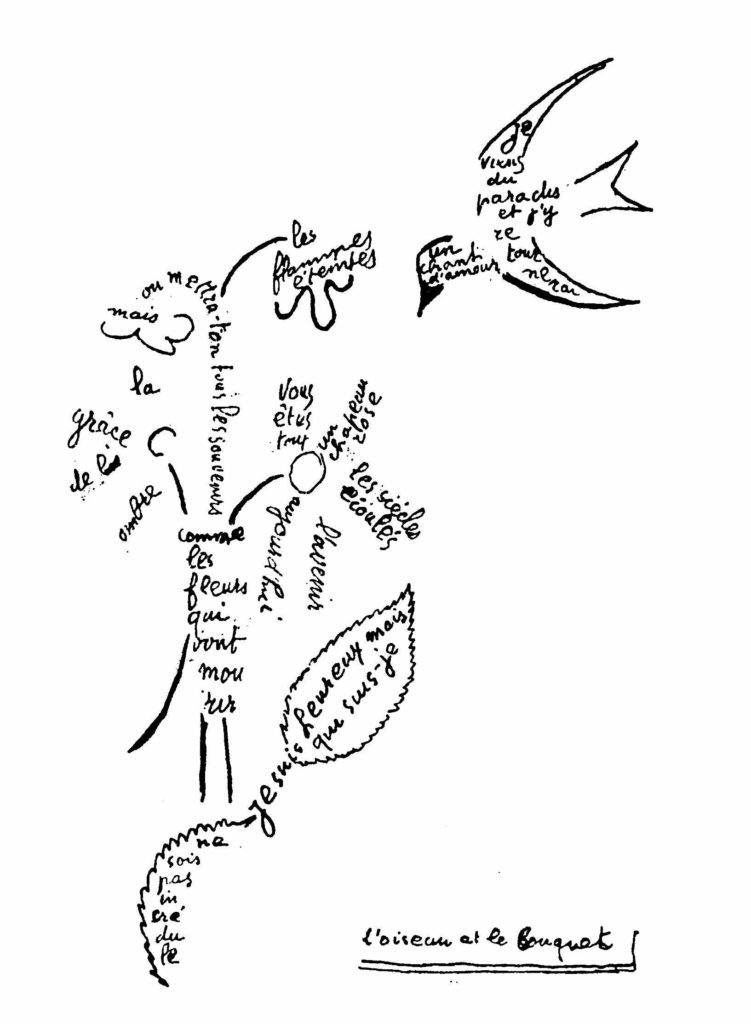

‘Où êtes-vous ô jeunes filles’, sighed Apollinaire nostalgically, in a particularly inventive ‘calligramme’ sent from his army post in 1914. And the names he lists form the wings of a dove hovering above a fountain: Mia, Mareye, Yette, Lorie, Annie, Marie. These by no means comprise a roll-call of his youthful conquests, of course. Perhaps they were the only ones he found it convenient to remember at that moment, or perhaps those particular names just fitted nicely into the poem’s space. In any case, it is curious to see the first three linked poetically with Annie and Marie, the girl he never made and the girl who was his mistress for six years, the governess immortalized in the Chanson du ma aimé and the painter who inspired the century’s most famous ballad, Le pont Mirabeau. The lumping together of these two with the also-rans is a not untypical manifestation of Apollinaire’s lifelong inability to distinguish clearly between infatuation and love. This weakness, which was partly responsible for the disasters that strewed the path of his relationship with women, turned out to be a source of strength to him as a poet: in that realm, the gross self-deception of the randy egotist was transformed magically into the romantic fatalism of the poète maudit, the mal aimé.

Who were the others, anyway? Mia appears briefly, in his pseudo-autobiographical allegory Le poète assassiné, as a pretty brunette eyed lustfully by the hero but indifferent to his attentions. Yette is doubtless the Mariette of the same story, a beautiful, dusky farmer’s daughter whom the irrepressible hero is about to seduce when her parents put in an unwelcome appearance. We know nothing about the mysterious Lorie, although her Germanic name suggests that she may have been a professional colleague of the Wilhelmine whose special talents he celebrates with obscene wit in one of his more unprintable poems. Mareye is Maria Dubois, the daughter of a local café owner at Stavelot in Belgium, where 19-year-old Guillaume spent a summer in 1899. A poem to her, written shortly afterwards, evokes the memory of passion under the pines, and no doubt a brief flirtation was consummated before a moonlight flit, necessitated by his inability to pay his pension bill, took him back to Paris. His next avowed passion was Linda; her unworthiness to feature as a feather of his amorous dove may result from her callous disregard of the pleas launched to her in a flurry of love poems during 1901. Also condemned to omission from the calligramme was Yvonne, a flirtatious neighbour whose teasing behaviour reduced him to take solitary pleasure, as he complains in a 1903 poem to her which accuses her of making love with someone else ‘pendant que sous le ciel/je tiens la chandelle’.

Who were the others, anyway? Mia appears briefly, in his pseudo-autobiographical allegory Le poète assassiné, as a pretty brunette eyed lustfully by the hero but indifferent to his attentions. Yette is doubtless the Mariette of the same story, a beautiful, dusky farmer’s daughter whom the irrepressible hero is about to seduce when her parents put in an unwelcome appearance. We know nothing about the mysterious Lorie, although her Germanic name suggests that she may have been a professional colleague of the Wilhelmine whose special talents he celebrates with obscene wit in one of his more unprintable poems. Mareye is Maria Dubois, the daughter of a local café owner at Stavelot in Belgium, where 19-year-old Guillaume spent a summer in 1899. A poem to her, written shortly afterwards, evokes the memory of passion under the pines, and no doubt a brief flirtation was consummated before a moonlight flit, necessitated by his inability to pay his pension bill, took him back to Paris. His next avowed passion was Linda; her unworthiness to feature as a feather of his amorous dove may result from her callous disregard of the pleas launched to her in a flurry of love poems during 1901. Also condemned to omission from the calligramme was Yvonne, a flirtatious neighbour whose teasing behaviour reduced him to take solitary pleasure, as he complains in a 1903 poem to her which accuses her of making love with someone else ‘pendant que sous le ciel/je tiens la chandelle’.

Annie and Marie, heroines of separate poems, seem ill at ease sharing the same one together: they were birds of a very different feather. Although Apollinaire boasted later that he had known Annie Playden ‘charnellement’ it seems more probable that kissing was the limit of his fleshly contact with this shy, puritanical English girl whom he courted with eccentric violence during his year as tutor with a German family. Annie fled from his lumbering importunities and terrifying rages to the comparative safety of England, where Guillaume pursued her twice, in 1903 and again the following year, until in desperation she emigrated to America, leaving instructions behind that no mail was to be forwarded to her. ‘Adieu faux amour’ he sobbed in the Chanson du mal aimé, but ended with an envoi complacent enough to reassure the reader that he was really only play acting: ‘Moi qui sais des lais pour les reines…/La romance du mal aimé/Et des chansons pour les sirens.’

Lays for queens and songs for sirens he knew indeed. Apollinaire has been our century’s most indefatigable poet of love. The erotic vibration which traverses his whole oeuvre offers amorous messages in all shapes and sizes, in every conceivable tone, for every taste simple or complex, ranging from a reasonable facsimile of the amour chevaleresque of a medieval troubadour through fairly straightforward romantic passion to an unprintable private world of anal-sadistic fantasy. There is an artificial flavour about Apollinaire’s sentimental poems which betrays the man who is incapable of loving and whose amour propre demands a scapegoat in the shape of malevolent fate. It does less than justice to that doleful ballad Le pont Mirabeau, written in 1912 after Marie Laurencin had finally left him for good. This banal theme of water flowing under bridges and love being swallowed inexorably by the passage of time is a perfect example of the lyrical tenderness and sad nostalgia which he could bring unerringly into play. But it rings hollow here. What a curious response, surely Le pont Mirabeau provides, with its hummable, strummable, languishing lines, to the brutal rupture of the only prolonged love affair of his life? One would imagine that Marie had simply drifted away gently with the tide; impossible to guess from the poet’s grave and sorrowful demeanour that she had finally fled because she couldn’t bear for one moment longer the gross behaviour of this jealous, tyrannical, unfaithful lover.

Apollinaire was genuinely incapable, it seems, of critical self-analysis, and so the farce of the mal aimé had to be played out, with its groans and sobs about betrayal and misunderstanding. The most independent of people himself, he could not endure any woman to show independence in relation to himself; a natural sensualist and boastful womanizer, he could suffer paroxysms of jealous rage at the mere suspicion that a girl’s eyes might be glancing in the direction of another man. The only wonder is that a high-spirited, intelligent and attractive girl such as Marie Laurencin should have put up with it for so long. ‘What people didn’t understand,’ she commented later on, referring to the reproaches that had been made to her by Guillaume’s friends for leaving him, ‘is that I was twenty-five and he was sleeping with all the women, and that at twenty-five you don’t stand for that, even from a poet!’

Apollinaire was genuinely incapable, it seems, of critical self-analysis, and so the farce of the mal aimé had to be played out, with its groans and sobs about betrayal and misunderstanding. The most independent of people himself, he could not endure any woman to show independence in relation to himself; a natural sensualist and boastful womanizer, he could suffer paroxysms of jealous rage at the mere suspicion that a girl’s eyes might be glancing in the direction of another man. The only wonder is that a high-spirited, intelligent and attractive girl such as Marie Laurencin should have put up with it for so long. ‘What people didn’t understand,’ she commented later on, referring to the reproaches that had been made to her by Guillaume’s friends for leaving him, ‘is that I was twenty-five and he was sleeping with all the women, and that at twenty-five you don’t stand for that, even from a poet!’

The final break with Marie occurred at what was probably a propitious moment for the poet, when his mind was beginning tentatively to search new horizons. He must have sensed that the sentimental comedy of false love he had played with such artistry was becoming as outmoded as the bell époque itself, the pre-cinematic, pre-radiophonic, pre-cubist, pre-Bergsonian era he was preparing to leave behind. ‘A la fin tu es las de ce monde ancient,’ he proclaimed in the first line of the poem Zone, written only fifteen months after the tear-drenched Pont Mirabeau.

The transformation of the art scene in Paris was the real challenge to Apollinaire at this time. Ever since ‘Baron’ Jean Mollet had introduced him to Picasso in 1904, he had been a warmly sympathetic commentator for the young painters in the pages of a series of newspapers and literary reviews. Undergoing a constant process of aesthetic education not only from Picasso, but from Max Jacob, Derain, Vlaminck and others, Apollinaire had come to feel moderately at ease in the perspective of fauvism and expressionism. But Picasso’s sudden demolition of five hundred years of tradition in European painting with his 1907 Demoiselles d’Avignon left the poet-critic in a state of perplexity, as did the subsequent development of cubist theory and practice. As late as 1911 he was still thrashing around wildly, describing cubism as a sort of cinematic art, and then the following year suggesting that it was already a thing of the past. But the enormous impact of the cubists’ contribution to the 1912 Salon d’Automne, reinforced by his faith in anything with which Picasso was associated, persuaded Apollinaire to become their official spokesman, although the halting terms in which he explained their work to the readers of Le Temps and other journals betrayed the fact that he had only the dimmest idea of what Picasso, Braque and the others were about. (As Duchamp, who knew him at that period, remarked: ‘Apollinaire was a very charming man. Of course he was always sounding off on all kinds of subjects he knew nothing about.’) Nevertheless, this was novelty, this was modernism, this was the new aesthetic, and he was there to raise the flag of artistic insurrection, to discover ‘pure art’ and invent orphism.

Since he had decided to put together a collection of his best poems for publication the following year, in 1913, it was an obvious idea to do the same thing for his scattered articles on painting. The result, in the cases of both Alcools and Les peintres cubistes, was a cocktail of many ingredients. The volume of poems contained work going back to 1898, but acquired an extra gloss of actuality at proof stage through the device of inserting the experimental Zone at the head of the book and another seminal poem, Vendémiaire, at the end. And the general appearance was streamlined by the elimination of all punctuation, also at proof stage. Les peintres cubistes underwent a similar process; originally to be entitled Méditations esthétiques: les peintres nouveaux, it consisted largely of rewritten articles unconcerned with cubism, and it was only at the last minute that the word ‘cubism’ was introduced at all into the text and the artists discussed in the book assembled arbitrarily into groups of theoretical allegiance.

In fact, Apollinaire was altogether rather awkwardly placed to be the spokesman of the avant garde in art and literature. He had no intellectual understanding whatsoever of painting, and in poetry he constantly felt the tug of the rich sonorities of the symbolism on which he had nurtured his sensibilities. It would not be unfair to say that he was totally innocent of any metaphysical or sociological curiosity. What seemed a final proof, even to his close friends, of his incurable frivolity, was his publication in June 1913, three months after Les peintres cubistes, of a weird manifesto, L’antitradition futuriste, in which a musical ‘merde’ is offered to a long list of professions, cultural centres and historical notabilities, and a rose awarded to Guillaume himself, his cubist friends and all the futurists. This gesture of solidarity with Marinetti seemed all the more puzzling when it was remembered that only a year previously he had castigated the futurists’ own manifesto for being ‘full of poverties of antiplastic ideas’. But Apollinaire was never particularly concerned to introduce logicality into his thought processes. The futurists had achieved notoriety since their first noisy appearance on the Paris scene, and Apollinaire had no intention of allowing himself to seem backward in supporting any promising novelty. Besides, L’antitradition futuriste was printed in Milan and intended to consolidate his position among the futurists there, not to win over his friends in Paris.

Cheerful brashness of such dimensions was irresistible. His charm and keen intuitive perception, possessed in equal measure, more than compensated for his naiveties, errors of judgement and confused opinions. He may not have understood art, but he could look at a painting with the eyes of a poet and interpret it lyrically- his essay on Picasso, with the marvellous opening words ‘Si nous savions, tous les dieux s’éveilleraient’, foreshadowed Breton’s poetical-critical approach to art interpretation. Alcools may be an amalgam of several embryonic plaquettes, but there runs through the book a sense of magical adventure and surprise that gives it a unity of feeling over and above the delicate balance achieved by a careful editing and blending of the disparate texts.

The protosurrealist quality of Apollinaire’s imagination had always been present: as early as 1903, with the apparition of the urchin through a London mist, at the beginning of the Chanson du mal aimé; or the hollow statue which, in Le poète assassiné, is sculpted underground in honour of the dead hero, its existence marked only by a laurel tree planted in the earth above it. Combined now with the experimental treatment of language that Zone and Venémiaire heralded, this ‘shock-imagery’ allowed him to make his full impact as the poet of the modern age. The first fruit of his search for a new poetic dimension was his ‘simultanist’ poem Les fenêtres. This was written for the catalogue of Delaunay’s 1912 exhibition of paintings in Berlin, and aimed, through the juxtaposition of unexpected images, to achieve the same effect in poetry that Delaunay’s new use of simultaneous colour contrasts envisioned in painting- a sense of speed and movement in a context of luminous space. Then, in June 1914, Apollinaire printed in his own magazine Les Soirées de Paris the ‘lyrical ideogram’ Lettre-Océan which was the prototype for all his subsequent picture-poems.

The protosurrealist quality of Apollinaire’s imagination had always been present: as early as 1903, with the apparition of the urchin through a London mist, at the beginning of the Chanson du mal aimé; or the hollow statue which, in Le poète assassiné, is sculpted underground in honour of the dead hero, its existence marked only by a laurel tree planted in the earth above it. Combined now with the experimental treatment of language that Zone and Venémiaire heralded, this ‘shock-imagery’ allowed him to make his full impact as the poet of the modern age. The first fruit of his search for a new poetic dimension was his ‘simultanist’ poem Les fenêtres. This was written for the catalogue of Delaunay’s 1912 exhibition of paintings in Berlin, and aimed, through the juxtaposition of unexpected images, to achieve the same effect in poetry that Delaunay’s new use of simultaneous colour contrasts envisioned in painting- a sense of speed and movement in a context of luminous space. Then, in June 1914, Apollinaire printed in his own magazine Les Soirées de Paris the ‘lyrical ideogram’ Lettre-Océan which was the prototype for all his subsequent picture-poems.

These ideograms, most of which were composed during the war, have come in for some supercilious criticism as being ‘something less than poems and a good deal less than paintings’. But it should be remembered that they were experiments, not definitive statements of poetic intent. And they corresponded to Apollinaire’s increasing preoccupation with the visual expression of poetic feeling, as he himself explained in the lecture he delivered in 1917 on L’esprit nouveau et les poètes: ‘One can foresee the day when, the gramophone and the cinema having become the only forms of printing in use, poets will enjoy a hereto unimagined freedom.’ Adding the tape-recorded to these liberating inventions, the sound-poets of today would surely find themselves endorsing Apollinaire’s forecast. And, on a less prophetic level, one can agree with Stefan Themerson, the author of the wittiest and most perceptive study of the ideograms yet published (Typographica 14, December 1966), that they constitute a valid extension of the lyrical feeling that underlies all his writing: ‘Apollinaire was a singing poet. And he didn’t cease to be a singing poet when, later, he tried to use the visual, spatial, qualities of signs to express the same, his own, thoughts and sentiments, to create the same, his, lyricism.’

Most of the poems that make up the collection Calligrammes, ‘poèmes de la Paix et de la Guerrer 1913-16’, are typographically conventional, though some, like La petite auto, contain ideograms in the body of the text to provide a more immediate visual impact for crucial passages. This particular poem describes the poet’s return from Deauville with his friend André Rouveyre on the announcement of general mobilization. Arriving in Paris, ‘nous comprîmes mon ami et moi/Que le la petitie auio nous avait conduits dans une époque/Nouvelle/Et bien qu’étant déjà tous deux des hommes mûrs/Nous venions cependant de naître’. But Apollinaite did not survive the war to witness the birth of that new era. The little movie film made in a coin-operated street booth that same day, showing the two friends talking happily to each other, was the last time that Apollinaire’s famous laugh would be recorded in peacetime.

Nothing has tarnished Apollinaire’s reputation as a poet so much as his wholehearted involvement in the war. His political naïvety was of formidable proportions; in 1916, for example, he could write to Tristan Tzaa as though the latter were a patriotic Roumanian and supporter of the Entente, and refuse regretfully to contribute to Tzara’s publication Dada because, despite what seemed to Apollinaire its patriotic respectability, it included German poets among its collaborators! The jolly poems he sent back from his training camp and the front are, indeed, hardly acceptable by any standards. The crassness of ‘Ah Dieu! que la guerre est jolie’ has been sufficiently commented on. There are great poems in Calligrammes, including Toujours and, of course, those two magnificent declarations of faith la Victoire and La jolie rousse. But the strongest body of poems to come out of Apollinaire’s war experience is to be sought outside the pages of Calligrammes and is inspired not by the war itself but by his successive emotional entanglement with two women. It was perfectly in accord with the tenor of his whole life that it was his obsessive need to prove his virility, rather than simple patriotism, that directly determined his involvement in the war. Both his enlistment in the army and his subsequent volunteering for front line duty were automatic responses to emotional rebuffs.

It is strange that La colombe poignardée et le jet d’eau, the ideogram representing a dove and a fountain, should have omitted from the bird’s feathers a particularly gaudy plume named Lou. Strange, because it was composed on December 24, 1914, and the whole of the second week of that month had been spent by Guillaume and Lou in the most deliriously prolong bout of love-making that the poet was ever to enjoy. Perhaps for the first time in his life he had reasons to keep a love affair secret. His letters to Lou have never been published, and only a selection of the poems has so far been made available. In a way the affaire with Lou was yet another sexual disaster in Apollinaire’s life, but the extraordinary nature of their relationship, in which an exacerbated eroticism temporarily overwhelmed them, acted as a kind of catalyst in his poetic imagination, and allowed him to prove that as a poet of love he was something more than the simple balladist, that he was also a truly great poet of carnal love, of the beauty of the female body.

As so often, it was a crisis that impelled Apollinaire into his new phase of poetic invention. He had met Loud in Nice, where he had gone after the outbreak of war, at an opium-smoking party, and had courted her tirelessly but fruitlessly for the three following months. Frustrated and wounded by successive rebuffs, he had enlisted and then sent her an artfully worded protestation of undying love. Lou, more than a match for Guillaume in perversity, immediately joined the new recruit in Nîmes, where he was undergoing training. When she returned, satiated, to Nice a week later, her thoughts immediately began to turn elsewhere; but Guillaume, of course, was no more capable now than he ever had been of conceiving that a woman might no longer desire him. And an avalanche of letters, often including poems, began to descend on Lou from Nîmes.

This frenetic correspondence produced an inspired flow of powerfully sensual poetry which was the most direct and genuinely felt lyrical expression that he ever achieved: the clear flame of erotic passion illuminated aspects of his nature that he had concealed hitherto under a cloak of gentle melancholy. It seemed that nothing would quench this flame. Even when she had made it abundantly clear in her answering letters that their sexual adventure was over, he continued his dithyrambics. When she taunted him with her new lover he reacted in a most curious way, consenting to a sort of imaginative voyeurism, in which she wrote him graphic descriptions of her sexual activities with her ‘Toutou’ and he replied in terms of vicarious gratification which on hardly dares analyse: ‘Lou Toutou soyez remerciés / Puisque par votre amour je ne sui pas seul / Et je nais de chacune de vos étreintes / Pensée vivante qui jaillit de vous.’

Lou unwittingly enmeshed him in an even more unlikely and pathetic adventure. After an overnight assignation with her in a Nice hotel during January 1915, Apollinaire had got into conversation with a young girl in the train that took him to Marseille on the first stage of his journey back to his unit. They had discussed poetry and exchanged addresses before saying goodbye. A last hopeless confrontation with Lou in Marseille, at the end of March, decided him to escape as soon as possible from Nîmes and its painful memories of brief erotic bliss: he volunteered for the front. On April 16, remember the stranger in the train, he wrote her a polite postcard, offering to send her a copy of Alcools. Her name was Madeleine Pagés. A box of cigars soon arrived as a present from her and a very peculiar correspondence indeed was under way. His letters to her (which we only know in expurgated form) became increasingly amorous as he gradually gained the confidence of this shy, sensitive young schoolteacher living with mother and younger brothers and sisters in the suburbs of Oran, Algeria. At the beginning, in a display of duplicity, which brings back memories of the old gay Gui, he continued to write in loving terms to Lou, and on more than one occasion he sent identical poems to both Lou and Madeleine. Only three months after their first exchange of letter he was actually proposing marriage to Madeleine. Completely captivated by now, she accepted, her mother gave her approval, and they were officially engaged! It now seemed perfectly normal to Apollinaire that, being engaged, he should be free to write to her in overtly erotic terms. There followed a series of twelve ‘secret’ poems, erethistic, tender, wholly convincing, which constitute a kind of primer of sexual education.

The rest of the romance of Gui and Madeleine is a tragicomedy. A Christmas leave with Madeleine and her family in Oran appears to have been a failure; probably the lubricious fantasies of this improbably courtship were doomed to evaporate in the cold light of physical reality. Back at the front once more, his letters to his fiancée continued to be filled with endearments, but the ‘mon amour jet t’adore’ became an increasingly parrot-like refrain, and the messages grew gradually cooler and more abstracted. February 10, 1916: ‘Don’t expect at the moment anything very amorous in my letters.’ February 24: ‘Write me about literary matters or any other matters that can elevate our thoughts’ Then on March 17 a shell fragment pierced his helmet and penetrated his skull. Nothing was to be the same again. Apollinaire lives for another two years and eight months, dying forty-eight hours before the armistice, of Spanish flu aggravated by a recent bout of pneumonia and the lingering after-effects of his head wound. But Madeleine had no part in his last remnant of his life, and Apollinaire’s last, great poem, La jolie rousse, was dedicated to another girl, Jaqueline Koln, whom he married after he was released from hospital. From that hospital he wrote to Madeleine on May 7: ‘I am no longer what I was from any point of view, and if I obeyed my instincts I’d become a priest or a monk.’ On August 26 he wrote: ‘Above all, do not come here, it would tax my emotions too greatly.’ His last letter to her is dated September 16, and demands the return of all the poems, notebooks and other documents he had entrusted to her.

A letter to his old friend, ‘Baron’ Jean Mollet, at the beginning of 1915, a few weeks after he had composted La colombe poignardée et le jet d’eau, shows how pleased he was with this achievement. ‘I have found new methods of poetry, more astonishing, and very much more complicated,’ he writes. And continues in the same breath: ‘Where we’re supposed to be going? Along the path of honour, old friend, and then after the war, along the path of glory, that’s where we’re going. . . Come on, don’t worry, we’ll get together again all right, and then if all goes according to plan it will be the Académie for yours truly.’ The Académie? An illusion, like love. It was the poetry that was real, in all its novelty, astonishment and complication.

To discover more content exclusive to our print and digital editions, subscribe here to receive a copy of The London Magazineto your door every two months, while also enjoying full access to our extensive digital archive of essays, literary journalism, fiction and poetry.

You must be logged in to post a comment.