Over sixty years on, it remains the most notorious act of wanton destruction in the history of modern British art. As is well known, the deed was done on the orders of Lady Churchill. A month after Sir Winston’s death in January 1965, she broke the news of the great portrait’s demise to her astonished youngest daughter, Mary (later Lady) Soames, and the latter’s politician husband, Christopher, who had been his father-in-law’s Parliamentary Private Secretary. They were on board the great liner Queen Mary sailing to New York when Lady Churchill made her confession.

Mary Soames recorded the confession in detail in her biography of her mother, published in 1979, two years after the latter’s death:

It was during the voyage to New York that my mother told Christopher and me that the Graham Sutherland portrait of my father was no longer in existence. We were both flabbergasted. We knew the picture had been sent to Chartwell not long after the presentation, and had been stored away there. But the information Clementine now imparted to us was a total surprise. She told us that Winston’s deep dislike of the picture, and the bitter resentment at the manner in which he had been portrayed, weighed more and more on his mind during the months that followed its presentation in November 1954, to such an extent that Clementine told us she had promised him that ‘it would never see the light of day’. As far as I know, she consulted no one about her intention, and it was entirely on her own initiative that some time in 1955 or 1956 she gave instructions for the picture to be destroyed. I do not believe Clementine ever specifically told Winston what steps she had taken: but her original pledge calmed him.

Exactly how the deed was done only became public knowledge fifty years later with the publication of a new biography of Lady Churchill by Sonia Purnell in 2015. In the Churchill Archives at Churchill College, Cambridge, Purnell came across a tape-recorded interview with Clementine Churchill’s long-serving private secretary, Grace Hamblin. In it, Hamblin described how she had offered to destroy the portrait in response to a plea for help from a ‘much exercised’ Lady Churchill. She and her brother, a gardener, dragged it out of the cellar at Chartwell ‘in the dead of night’ (as if it were a corpse rather than just an unwanted picture), loaded it on to his van and drove it to his house, some miles away. There they lit a bonfire in his back garden and burnt it. Hamblin reported its cremation to Lady Churchill the following day. ‘Lady C and I decided we would not tell anyone’ (and the method of destruction does not seem to have been subsequently revealed to the Soameses). A portrait that had known only controversy during its short life met its end in these rather absurdly melodramatic circumstances.

Interest in the picture did not of course end. On the contrary it grew, if anything stimulated by the mystery surrounding the portrait itself. Surviving images (photographs and Sutherland’s preliminary sketches) have kept it prominently in the consciousness of the nation over the decades, alongside so many other photographs and portraits which illuminate the varied and tumultuous dimensions of the great statesman’s character.

Sutherland did not set out to belittle Churchill whom he admired, despite being a Labour voter. The two men got on well as work on the portrait progressed. Initially, Lady Churchill liked Sutherland’s depiction of her husband (‘I can’t thank you enough’, she said to the artist with tears in her eyes after it had been finished, but before Sir Winston had seen it), later changing her mind completely in the light of his horrified reaction to it.

‘I look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand’, Churchill told his private secretary, Anthony Montague Browne. His intense dislike of the portrait – which in the view of his biographer, Roy Jenkins, ‘passed the bounds of rationality’ – may have led to its destruction, but the charge that it gave a totally misleading impression of him in old age cannot be sustained. In February 1955 a senior Foreign Office official, Evelyn Shuckburgh, noted in his diary that he had encountered Churchill ‘slumped in his chair, looking just like the Sutherland portrait’.

Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran, put his finger on the central difficulty in the account of Churchill’s reaction to the portrait which he included in his diary. Churchill, he recorded, ‘does not like criticism, written or pictorial. A lot of his time since the end of the war had been spent arranging and editing the part he will play in history, and it has been rather a shock to him that his ideas and those of Graham Sutherland seem so far apart’. Churchill understandably was interested only in being depicted as the national hero that he will always remain; Sutherland, as he said so often, painted him as the man he encountered in the weeks before his eightieth birthday. He explained that he could only ‘paint what he saw’.

Churchill’s damning personal verdict on the picture has not been accepted by posterity. Last year, one of the country’s leading historians, Simon Schama, gave Sutherland’s portrait the dominant place in an acclaimed television series, accompanied by a book, The Face of Britain: The Nation through Its Portraits. ‘With the exception perhaps of the paintings of the Duke of Wellington by Goya and Thomas Lawrence’, he writes, ‘Sutherland accomplished the most powerful image of a Great Briton ever executed’. It deserves the deep interest and respect with which it has been regarded for over sixty years.

The picture does not exist today, however, merely in photographs and in the artist’s sketches on which the portrait was based. What both the experts and the general public do not realise is that the portrait was painted again with care and affection, keeping as faithfully as possible to the original in every respect. Hitherto generally unknown to the world at large, it was re-created by a remarkable naturalised Englishman, Albrecht von Leyden, who felt strongly that the famous, controversial portrait ought not to be lost for ever. Thanks to him, a rebirth took place.

***

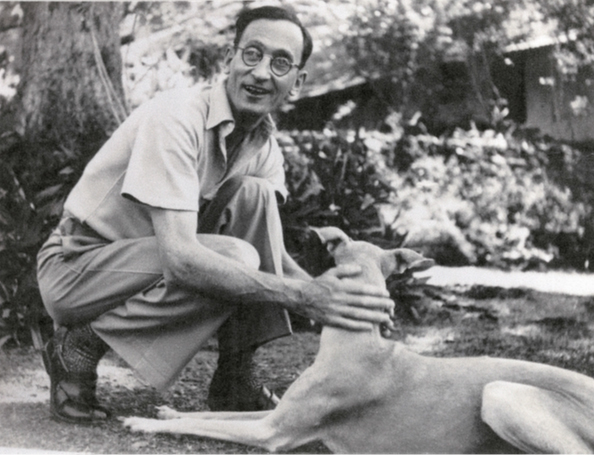

No one admired Winston Churchill more fervently than Albrecht Robert von Leyden MBE (1905-94), a German with Jewish heritage who became a proud British citizen in 1938 during a long and successful career as a businessman in British India. Like his fellow citizens in Britain and other countries around the world, he felt an intense sense of gratitude for Churchill’s leadership and courage during the Second World War. The victory of his adopted country and its allies over Germany, the country of his birth, rid Europe of the Nazi tyranny to which he and his family had always been totally opposed.

The von Leydens were noted in each generation for their talent, culture, liberal views, and sense of public duty. Albrecht’s grandfather, Professor Ernst von Leyden, was a famous Berlin physician who won the trust and gratitude of the leader of political liberalism in the newly united Germany, Kaiser Frederick III, son-in-law of Queen Victoria, whose early and painful death from cancer in 1888 opened the way for Kaiser Wilhelm II’s aggressively militaristic regime. A statue of this brilliant doctor, paid for by public subscription, still stands in Berlin. Albrecht’s father was a senior civil servant who was side-lined when Hitler came to power; Albrecht brought him to India just before war broke out. One of his brothers became a distinguished teacher of philosophy in British universities; another, Rudi, was Albrecht’s companion in Bombay where he worked as an artist and art critic for The Times of India.

From Professor Ernst’s day onwards the family was also known for its passionate devotion to an activity that demands great skill and stamina: mountaineering. Notable exploits were recorded in the pages of The Alpine Journal, the publication of the Alpine Club to which Albrecht and many of his relatives belonged. Albrecht himself was a prominent contributor to the family’s formidable reputation, as his obituary in The Alpine Journal written by a close English friend and fellow mountaineer, Peter Wormald, makes clear. After his own climbing career ended, he remained closely involved in the sport, becoming Secretary of the Bombay branch of the Himalayan Club and hosting members of the 1953 Everest expedition. Albrecht was a man who knew always how to enjoy himself; he brought his sense of fun to the precipices and pinnacles of the world’s most challenging mountains to the delight of his companions.

He moved to Bombay in 1928 to play a prominent part in building up the Indian interests of Germany’s leading manufacturer and distributor of photographic products of all kinds, Agfa, which had been founded in 1867 (continuing its expansion in the second half of the twentieth century, it merged with other firms to become today’s international giant, Agfa-Gevaert). Albrecht’s progress as a businessman was assisted by his sensitivity and enlightened views: ‘his relations with members of the various races, creeds and castes in India were admirable and laid the foundations for his later commercial success’.10 Britain benefited directly from that commercial success. Nazi pressure was exerted on Agfa to get him sacked in 1938; a flourishing British photographic firm, Johnsons of Hendon, promptly made him their representative in Bombay, reinforcing his affection for Britain. ‘By the end of the war he had built up a successful business with branches in other Indian cities’.

The successful entrepreneur was also a man of compassion. ‘He believed intensely in principles of justice and fair play’. For many years he was Chairman of the Bombay Relief Association, providing shelter and medical care for elderly destitute men. For his large contribution to its work, he was awarded the MBE in 1968, the year he left India following his retirement from business, and settled with his wife, Margit, in Partenkirchen, Bavaria, where his mother was still living in the house built by his father.

Apart from mountaineering and his family, his principal passion in private life was painting. Wholly self-taught, ‘he was a talented artist and painted hundreds of pictures in oils and watercolours, mostly of Indian, Himalayan and Alpine scenes’, some of which remain in the possession of his step-daughter, Kuki Hahndel, who is married to Peter Trew, a former Conservative MP for Dartford (1970-February 1974). Albrecht had also gained great experience as a portrait painter. In his later years his painting kept him well occupied, particularly after he had established a studio in his house at Partenkirchen after his wife’s death in 1978. He was well qualified for the task that he was to take up, and had the time to carry it out with painstaking care.

***

It was at Partenkirchen the following year that he learned of the destruction of Graham Sutherland’s portrait. The tragedy became known to the world at large for the first time on the publication of Mary Soames’s life of her mother in 1979, having been kept secret after her confession to the Soameses in 1965. Albrecht recorded his deep unhappiness on hearing what had happened, at the start of a detailed account of his reconstruction of the portrait, entitled The Churchill Portrait: Story of a Painting, which he subsequently circulated to a number of relatives and which describes brilliantly his research and his personal feelings as he prepared to carry out his self-appointed task, assisted at one crucial juncture by his brother Rudi who met Sutherland and his wife in the south of France, gaining important information from them. Albrecht began his account in sombre vein:

The news stunned me. I had been an admirer of Graham Sutherland ever since my late wife and I visited the rebuilt Cathedral at Coventry and saw its most beautiful tapestry ‘Christ in Glory’ after a design by Sutherland . . . The other occasion which confronted me with the art of G.S. occurred in 1977 when I visited an exhibition of his portraits, organised by Dr John Hayes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery. I was captivated completely by the expressive conception and execution of his portraits. Of course, one portrait was missing, the one of Sir Winston Churchill . . . But theexhibition included many sketches in oil and pencil, made by G. S., which all showed the immense care he took and the labour he underwent to produce this masterpiece.

Thus, my knowledge of what I had seen of the art of Sutherland was the cause of [my] feeling completely stunned by the news that this portrait had been wilfully destroyed. By my own experience as an amateur painter, I could feel the agony any artist would suffer to see his work destroyed . . . . I wondered how great and inspired people like Sir Winston and Lady Churchill, for whom I always had maintained the greatest admiration, could be so entirely oblivious to this aspect of their action.

My further reaction seemed strange . . . I felt that, as a protest to the destruction of the portrait, an effort should be made to recreate it. As nobody else appeared to have been inspired in this manner, I came to the conclusion that I should make an attempt.

This would be by no means his first venture of this kind. He had made copies of paintings or drawings of great masters including Rubens, Rembrandt and Van Gogh. With the help of an art student at the Courtauld, he now obtained a copy of a colour photograph of the Churchill portrait reproduced from a colour slide, ‘the only good photograph ever taken of the portrait . . . [probably done] immediately after the presentation of the portrait in Westminster Hall’. Albrecht also acquired a useful article about the portrait by the journalist, Ian Jack, which had appeared in The Sunday Times. But there were problems with the photograph. ‘The colour of the eyes was not at all discernible. Also it showed different tones of colour in the lower part of the background from the upper part. Another problem presented to me was the actual size of the portrait which was not mentioned in The Sunday Times’.

My research began by studying again very carefully the catalogue of the 1977 exhibition and the portion of it devoted to the sketches made by G. S. for the Churchill portrait. Suddenly I discovered on one of his sketches lent by the Beaverbrook Foundation certain handwritten notes, evidently made by the artist while sketching the eyes, hands and other features of Sir Winston Churchill. I got hold of a magnifying glass and, with some difficulty, was able to decipher the faintly scribbled notes to read as follows:

Done while W.S.C playing cards with Soames. Chequers 14th Nov.1954.

1. The eyebrows appear almost corn colour.

2. Under cheek bones pink.

3. Jowls pink.

4. Upper lip cream.

5. Overall impression pink with cream lights, i.e. over temples and eye lids.

6. Shadows (under chin) very grey, very pale. Side of eyes pinker.

Then, there was a complete and well-executed sketch of one eye with lines pointing to the left and right sides of the pupil and notes saying ‘darker’ resp. [sic] ‘light blue’.

These notes, somewhat miraculously, gave me the almost exact description of the colour and tone values of the face and eyes of the portrait. But what of the background, how and in what way was it really painted? Here again, I was fortunate in my research. Re-reading The Sunday Times article, I found the following passage:

For two days the late Hans Juda, formerly owner and editor of The Ambassador magazine, and his wife had the portrait in their possession, an odd and hitherto unrevealed event which came about after Hans Juda offered to take the painting off Churchill’s hands. It was delivered to their London home, and two days later shipped back to Churchill: it is thought Churchill had a guilty conscience about actually giving the portrait away. Mrs Elsbeth Juda had taken some colour slides. We [i.e. the reporters] took them round to Sutherland at his room at the Connaught Hotel. Too black, said Sutherland, or too blue, or too brown. He remembered the background as khaki – “pure yellow ochre with a touch of umber”.

So, all of a sudden, I had been given almost all the information I needed by the artist himself, like a voice from the beyond! One mystery remained unsolved, the actual size of the painting. Again a strange circumstance came to my rescue. When living in India, my brother Rudi and I were always in very close contact with art circles in Bombay. Indian painting experienced a revival in the thirties when the skill of Professor Langhammer, a professional artist who had emigrated to Bombay from Vienna, inspired the many young Indian artists to embark on new ventures of modern art. There were many of them, and Rudi and I encouraged them financially by establishing an Artist’s Fund and creating a permanent Art Salon which was and still is available without any charge for one man art exhibitions.

One of the young and talented artists was Raza, a Mohammedan who later emigrated to France, established himself successfully in Paris and married a French girl, herself a painter.

Rudi kept in permanent contact with him and late in 1979 visited him in Gorbio, in the south of France, where several artists maintained cottages or houses for the summer vacations. During this visit my brother met Mr and Mrs Sutherland who had a house in Menton. When Rudi expressed his distress over the destruction of the Churchill portrait, Sutherland said that, quite apart from the vandalism of the act, it was a violation of an agreement that the portrait, after the death of Sir Winston and Lady Churchill, should be returned to Parliament. An astonishing revelation! And Mrs Sutherland, whom I met in London in 1981, confirmed to me that this was in fact true, that the Churchills had no lawful right to destroy the painting.

Graham Sutherland died on 18 February 1980. However, as Rudi had met his widow in Menton, it occurred to me that he could ask her if she might remember the measurements of the painting. This he did and, after a long delay, Mrs Sutherland replied from her rooms at the Connaught Hotel, stating the exact measurements as being 147.3 x 121.9 cm, or 58 x 48 inches. I received this important information in January 1981. Just at that time, a fully illustrated biography of Graham Sutherland by Dr John Hayes was published in London. It included not only several excellent colour reproductions of portraits but the book jacket showed very prominently a perfect black and white reproduction of the Churchill portrait. It showed details more distinctly than the colour reproductions in The Sunday Times.

Having made these very thorough preparations, assisted by some lucky breaks along the way, Albrecht was ready to begin – and as he worked, he found himself reflecting on Churchill’s indomitable character, as depicted by Sutherland, and on the profound emotions that the great man both stirred and expressed so memorably to strengthen the resolve of the people of Britain in 1940. They came to dominate Albrecht’s thoughts as he devoted himself to the recreation of the portrait, described in the concluding sections of his absorbing memoir of the reconstruction:

I felt now that my search had come to a successful end and that I could embark on the venture of recreating G. S.’s masterpiece. I began by making pencil sketches of the head and details of his features as reproduced in such detail in the 1977 catalogue. Slowly I came to know my subject better and when I returned to Partenkirchen, where I was then living, in February 1981 I ordered a canvas of the required size and started to paint.

As I went on with my task, I became gradually aware of the emotion which directed Sutherland and the conception which the artist wanted to express, the face of a man inspired by the power of firm resolution and of defiance – defiance of a wicked enemy, Hitler, and the resolution to win at all costs. I suddenly realised how Sutherland visualised Winston Churchill sitting down in his seat in the House of Commons after one of the powerful speeches he made in 1940 – speeches which suddenly revived hope in the hearts of all free people in the world, that Hitler had not yet won the war after the fall of France and that he would be defeated in the end. Harold Nicolson, who was a Member of Parliament and also served in Churchill’s Government, wrote in his diary:

This afternoon Winston made the finest speech I have ever heard. What a chance! The whole of Europe humiliated except us. And the chance that we shall by our stubbornness give victory to the world. The Prime Minister by putting the grim side foremost impresses us with the ability to face the worst. Thank God, we have a man

like that. I have never admired him more. I think that we have managed to avoid losing this war. We shall win, I know that. I have no doubt at all.

I think these diary notes of Harold Nicolson’s represented the mood of the whole nation who were inspired by Churchill’s power of speech. His resolution to win the war and his defiance when he told the nation: ‘We shall never surrender!’ feature in Sutherland’s portrait. This was the expression he gave to Churchill’s face, the stubborn look of resolution and defiance.

My conception of the portrait was in a way confirmed by what Sutherland himself has said in conversation with Dr Hayes which I found printed in the 1977 catalogue. He said: ‘The question of likeness, of course, goes far beyond the simple question of physical likeness. One draws or paints in a way which one’s emotions always direct. Emotions can alter the form itself, to a greater or lesser degree. Those who have wielded power are bound to be interesting to study. I do find it immensely fascinating to deal with people who have had pressures put upon them or who have had the character necessary to direct great enterprises’.

This, I think, was a direct reference to Winston Churchill.

Perhaps I could detect one other feature in the face as painted by Sutherland: contempt. Winston Churchill was too great a man to feel an emotion like hate for a man like Hitler. All he felt was contempt. And this also seemed evident to the discerning eye.

With all this in mind, I felt that if I were able to recreate the portrait with this expression of defiance, resolution and contempt, which I felt sure had been the purpose of Graham Sutherland, then perhaps the object of my own attempt might be achieved.

It took me altogether three months to complete the recreation of the portrait, incidentally the same period of time that Sutherland required for the original. And when I had finished, I wrote with my brush on the back of the canvas: ‘We shall never surrender!’ W. S. C. 4 June 1940.

Thus ends the story of a painting!

***

The portrait was reborn in 1981 and, as Albrecht’s memoir makes clear, in reconstructing it he sought to honour both Churchill and Sutherland. Ten years later, Albrecht, who had moved to Luzern, Switzerland, in 1982, presented it to the Carlton Club, well-known for its close connections with the Conservative Party which had renamed one of its principal rooms in Churchill’s memory after his death. Though no correspondence relating to the gift has been found in the Club’s archives, the minutes of its General Committee make clear what happened. On 23 April 1991 the Club’s Chairman, Lord Whitelaw, informed the Committee that the portrait had been offered to the Club: ‘the Committee asked the Chairman to consult Lady Soames and Mr Winston Churchill MP in the first instance, emphasising the merits of housing the portrait at the Club from a security point of view’. Albrecht was thanked for his generosity. At a meeting of the Committee on 10 December 1991 a letter from him expressing appreciation was read to the Committee and it was minuted ‘that the portrait would be kept at the Club in safe-keeping and would not be displayed for the time being. The Chairman agreed to invite Lady Soames to visit the Club to view the portrait’. The last reference to the portrait appears in the Committee’s minutes of a meeting on 25 February 1992: ‘The Chairman reported that Lady Soames had viewed the copy of Sutherland’s portrait of her father and was content to let the Club act as its future guardian’.

The gift to the Carlton Club was the subject of a snide piece in The Sunday Telegraph in 1993, which referred to the work having been painted by ‘a German – of all people’. In a spirited response, Albrecht’s nephew, James von Leyden, pointed out that his uncle (whose mother was Jewish) had been a refugee from Germany who had served in British auxiliary forces during the Second World War. He also said that Albrecht was an even greater admirer of Churchill than he was of Sutherland. The re-creation of the portrait was a homage as much to the sitter as it was to the original painting.

It was Albrecht’s hope that the portrait would be hung in the Club’s Churchill Room. A photograph, taken apparently soon after its arrival, shows the portrait on the wall of another room. It was then stored in the Club’s attic where it remains.

Albrecht von Leyden died on 3 January 1994. At his funeral in Luzern the world famous flautist, James Galway, a friend and neighbour, played works by J. S and C. P. E. Bach, Gluck, and Telemann.

Aster Crawshaw is a corporate partner at a law firm in the City of London. He read History at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge, where he was a senior scholar. He worked with his co-author, Alistair Lexden, at the Conservative Research Department in the mid-1990s and was Conservative candidate for Sheffield Healey at the 2005 general election.

Alistair Lexden is a Conservative peer and the official historian of his Party. He is co-author of The Carlton Club 1832-2007. Full details of all his recent publications, and of his contributions to the work of the House of Lords, can be found on his website, http://www.alistairlexden.org.uk. Outside political history, his areas of special interest are Northern Ireland, constitutional affairs, independent education and gay rights.

You must be logged in to post a comment.